News that made a difference for Texas students

/

In the first week of this new year, we want to look back at some of the most consequential education stories—for both public schools and alternative schools—in Texas in 2016. As we look back, we see three major political flashpoints, and also some promising trends and innovations growing out of the alternative school scene in our area. Both flashpoints and innovations are listed below, with links for finding out more information about each.

Political Flashpoints

- At the moment we were compiling this list, the Austin American-Statesman published a report revealing that “School districts across Texas pulled in lackluster preliminary grades under the state’s new letter-grade accountability system.” The new system, which won’t be fully implemented until next year, is based primarily on standardized testing and got a lot of complaints and pushback from school districts—including Austin ISD—even before the preliminary grades were released. Looks like this grading system will be an issue to watch going forward into 2017 and beyond.

- August 2016 marked the 50th anniversary of the tragedy of the sniper attack on UT’s campus, the first modern-day mass shooting. August also marked the beginning of so-called “campus carry” at Texas’s public colleges.

- A series of investigative pieces by the Houston Chronicle revealed that the Texas Education Agency may have mandated low special education enrollment in public schools, leading to the denial of crucial services for many children and saving the state billions. The investigations are ongoing.

Trends in Alternative Education around Austin

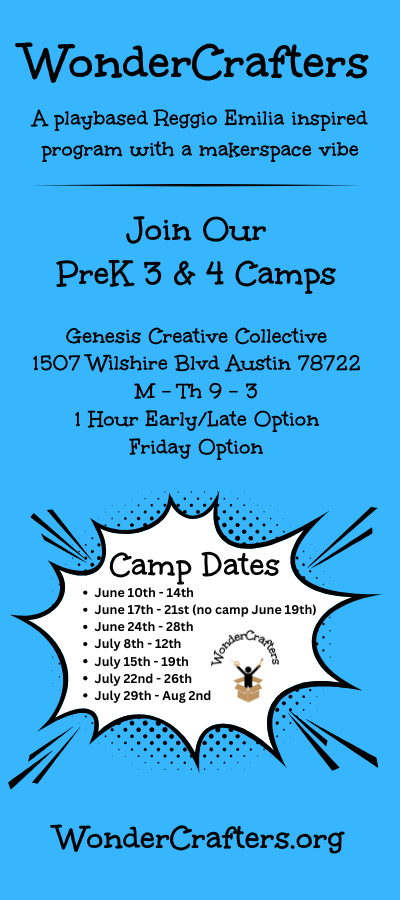

- We’ve seen a boom in outdoor and nature-based preschool education in the Austin area, with a new family program—Tinkergarten—as a welcome addition. You’ll find preschools that put nature education high on their priority list in our school directory.

- Entrepreneurial education and schools that specifically focus on preparing kids for the changing economy, which will require more creativity and problem-solving skills, are definitely on the rise.

- Inclusiveness, including gender inclusiveness, is something more and more alternative schools pride themselves on.

If there are trends or major issues in Texas education you want to see explored on our blog, let us know in the comments below, and we’ll make an effort to address them in 2017. Here’s to a happy new year for all Texas kids!