Joy is the bottom line: Entrepreneurial education in Austin

/Young entrepreneurs at the annual Acton Children’s Business Fair

Shelley Sperry is a staff writer at Alt Ed Austin. An entrepreneur in her own right, she also works as a writer, researcher, and editor at Sperry Editorial.

When you hear the term “entrepreneurial education,” you may first think about old-school extracurricular clubs that teach kids through hands-on projects—programs such as Junior Achievement and 4-H, or even the annual ritual of Girl Scout cookie sales. What I’ve learned by investigating schools in Austin is that entrepreneurial education is a big-tent concept that includes a diverse mix of well-established and brand-new ventures. Some find the label limiting, but it’s useful for identifying schools that share a few core similarities:

- An emphasis on projects in which kids make, market, and sell products that link them to customers and the community outside the school

- A holistic approach that integrates mind, body, and spirit in the learning process

- Elimination of separate, “siloed” subjects (math, science, language arts, social studies) in favor of integrated learning of all content via entrepreneurial projects

- Use of approaches from the start-up business world to structure groups, projects, and timelines

- De-emphasis on teachers and direct instruction in favor of mentors and guides who help students make their own decisions

- An interest in building kids’ sense of themselves and their work as tools for making the world a better place

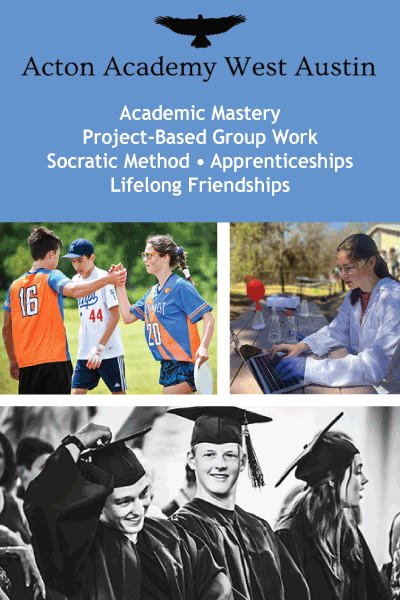

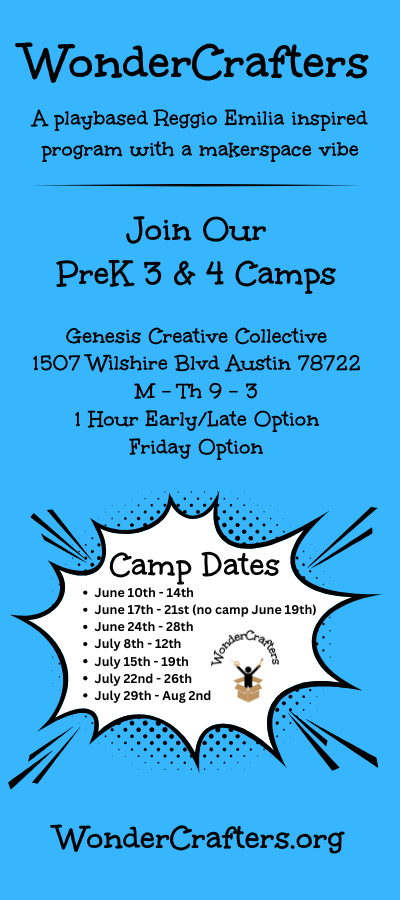

Austin programs that fall into this big tent include Acton Academy, Kọ School + Incubator, Sansori High School @ Whole Life Learning Center, and WonderLab.

When I interviewed Jeff Sandefer of the well-established Acton Academy and Kristin Kim of Sansori High School, which will be opening to its first class in August this year, I was struck by the fact that both approaches emphasize the importance of each student’s personal journey toward self-confidence and self-knowledge. This is something I normally would associate with twenty-somethings rather than kids in elementary, middle, and high school, but it demonstrates an essential part of the entrepreneurial education philosophy. Kids are respected as capable, contributing members of the community, even as six- or seven-year-olds.

Acton Academy’s approach is built around the notion of the “hero’s journey” usually associated with classic literature. Sandefer argues that each Acton student should understand himself or herself as on a life quest, rather than merely acquiring a set of skills or facts.

A student-led discussion at Acton Academy

“It’s more about learning to persevere, to fail and get back up, to treat people with kindness, and to listen before talking,” he explains. “We start with kids as early as six and go all the way through high school, cultivating these traits. They earn more and more freedom as they get older. They learn that the better you treat people, the harder you work, the more freedom you have.”

Acton’s Children’s Business Fair is the biggest such gathering in the country and has become a major community event in Austin each fall. The fair hosts more than 100 booths and brings together students not only from Acton’s elementary, middle, and high schools, but also from across a spectrum of Austin schools and homeschooling environments who want to create products or services and market them to customers while learning business, academic, and life skills.

With Sandefer’s blessing, other educators are creating schools based on the Acton model in other parts of Central Texas, throughout the United States, and beyond. The first graduate of Acton Academy Guatemala was recently accepted into the University of California at Berkeley with a triple major in math, biology, and biosciences.

Along with local and national business leaders who support the Kọ School, founders Michael Strong and Khotso Khabele believe that all people in the world should be able to live their lives creatively and productively. In other words, everyone should have the opportunity to behave like entrepreneurs: innovating and adding value to society. They believe that happiness comes from challenging work in which individuals create something meaningful, and they argue that the best path to this kind of life is through a Socratic method of questioning and learning how to teach oneself. The Kọ School + Incubator is designed to “blur the boundary between school and the outside world.”

WonderLab describes itself as a true incubator and is less a full-time school than a gathering place that puts like-minded, entrepreneurial kids together to help each other. Students identify their own goals and the resources and skills they need to reach those goals, and then they form teams that are assisted by an adult guide. Team members support each other and work together for a few hours each week. But even in this very practical world of achieving specific project goals, the overarching philosophy is that kids will end up exploring and defining themselves. They will be “on the path to figuring out the intersection of their gifts, their passions, and what the world needs.”

An image from the Sansori High School website that expresses one of the central principles of the program

Kristin Kim, who is bringing her Sansori educational philosophy to Austin this year in partnership with the Whole Life Learning Center, puts holistic learning at the center. “I give talks at colleges in the U.S. and U.K., and I hear that the students in their twenties don’t know what to do with their lives and are searching. We can offer children a different way of learning so that one benefit is getting a clear sense of what they love and how they can apply it in the world. They leave high school with skills and with self-knowledge.”

Kim says that confidence and joy are the hallmarks of her approach. A sense of integration of the individual and the world outside the classroom seems to be crucial too. By way of example, Kim describes students who made beeswax candles for sale, which seems like a simple learning-about-business project, but became something much grander in its implications. Students learned important lessons in science, math, and language arts as they made and marketed the candles. “We also connected their activities with how the universe works through the structure of polymers and the ecology of bees, and connected it with their own physical bodies in terms of other cultures’ understanding of the medicinal value of honey.”

I still think the word “entrepreneurial” works to describe these diverse Austin schools, because each does develop in students a taste for creating and innovating, whether in business, science, the arts, or other pursuits. But I would also say that a “whole child” focus that brings a spiritual element to the table is just as important, and something I hadn’t expected.

As Kim says, “What we’re doing is allowing students of all ages to experience learning not just through their brains or minds, but through their bodies and hearts. They then see themselves differently and understand the co-creative role of each human being. When you get a deep understanding of the unity between inner and outer worlds, joy is a natural consequence.”

Shelley Sperry