Becoming established

/Caitlin Macklin, 9th Street Schoolhouse mentor and founder, recently visited the famed Free School in Albany, New York. In this guest post she shares some images and insights she gained there about building a democratic school community and culture over time.

“Wow. I’m really here. The place of my inspiration.”

This summer I made a pilgrimage to Albany, New York, to visit the Free School. This decades-old institution has long been a guiding light for me. It was my first introduction to the concepts of non-mandatory classes, democratic participation by students in conflict resolution and school governance, and putting children truly at the center of education.

As a new teacher (of four years) and a new school (into our third here at 9th Street), the thing that sank in most for me is the sense of being established that the Free School exudes. The feeling of rootedness settled in as I climbed up narrow stairways and stood on wood floors with lived-in scuff marks—I mean, even the disaster area of the summertime kitchen made my heart ache to have a SPACE to CREATE.

I currently teach out of my home on East 9th Street. This year, Laura Ruiz joined the Schoolhouse, and collaborating feels great! We intend to grow slowly but surely into a larger community of families more the size of the Free School, about sixty kids with a staff of five or six. During the visit to Albany, I was just soaking it in—in awe of what people have built together, just “making it up as [they] go along,” doing what makes sense, not what a bureaucrat tells them to do. Working with families, giving kids opportunities and mentoring, so they may discover and grow while staying whole, messy, in touch with their inner selves.

YouthFX program participants rehearse scenes for their summer narrative film project in the great room at the Albany Free School.

YouthFX program participants rehearse scenes for their summer narrative film project in the great room at the Albany Free School.

I have put so much thought into how to implement in my teaching and in the Schoolhouse structure the lessons AFS has learned that to see it and know it as a place with a particular community and history helped me understand their context and refocus my efforts in recognizing and building on what our community’s strengths are. Getting to ask Bhawin, a longtime teacher, some of my burning questions about the how of their lives together, talking with him about their process of becoming the school they are now, gave me an infusion of patience with our process.

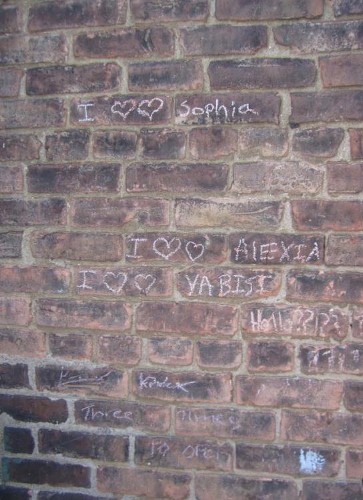

Bhawin stepped out of the frame as we discussed the community-created Rules on the wall behind us.

Bhawin stepped out of the frame as we discussed the community-created Rules on the wall behind us.

I left feeling encouraged to give time to developing the particularities of our program, staying true to who we are as teachers, youth, parents—as people—and to respond from those real relationships to create better and better opportunities for living and learning together. Part of that is my commitment to making democratic, learner-centered education accessible to people in Austin who might not be able to afford it. In addition to an affordable tuition and part-trade options, I’ve also been working with the Education Transformation Alliance to collaborate on creating a scholarship fund.

Making meaningful education available to more folks in Austin is what our work with the ETA is guided by. And I think finding meaning is what this shift in education in Austin is all about: this is a growing movement of people who want more than cookie-cutter experiences for their kids and their lives. People in Austin are more than ever feeling acutely that the current system is just not fulfilling their dreams for their kids. We all want our youth to live lives that are prosperous and flourishing, and I want the young people in my program to identify and define that success for themselves within a strong web of community, where they are known and where they know what resources are available to them.

We are seeking meaning in our learning and in our relationships, and we are creating institutions that respond, that put down roots, that take time to get established, that work together. I invite you to find out more about the many alternatives available across the city on the ETA School Tour this Saturday, Oct. 20!

For further reading on the Albany Free School, pick up any of Chris Mercogliano’s works, watch Free to Learn by Bhawin Suchak and Jeff Root, and check out the school’s website or this blog post from an intern.

Caitlin Macklin