A garden, a dream, and the sun

/Carly Borders, director and guide at The Soleil School, joins the Alt Ed Austin conversation with this guest post about her journey as a parent, professional educator, and entrepreneur toward a new model of education called the Whole Learning Framework.

Imagine planting a large and diverse garden. You’ve planted all types of flowers, vegetables, fruits, and herbs—all at the same time. Suppose you cultivated them all in the same way, ignoring each plant’s unique requirements? Every day, you water all of the seeds the same amount. You give them all the same amount of fertilizer. A few of the plants are sprouting and appear to be doing fairly well. But you notice that the rest are weak and brittle, if they’re growing at all. Yet you continue to do things the same way, all the while wondering why all of the plants aren’t thriving.

Imagine planting a large and diverse garden. You’ve planted all types of flowers, vegetables, fruits, and herbs—all at the same time. Suppose you cultivated them all in the same way, ignoring each plant’s unique requirements? Every day, you water all of the seeds the same amount. You give them all the same amount of fertilizer. A few of the plants are sprouting and appear to be doing fairly well. But you notice that the rest are weak and brittle, if they’re growing at all. Yet you continue to do things the same way, all the while wondering why all of the plants aren’t thriving.

But what if you had more flexibility? What if you got to know each flower and each peapod more intimately? You’ve taken great care to understand the different plants and the care it takes to bring each one up healthy to flower in its own way. And so you plant them according to their unique needs—at the right times, with the right amount of sunlight and the right kind of food. After a time, they’re all sprouting. They’re being given what they need, because they’re being treated with the respect they need. And look at the colors that begin to emerge! From the pinks of the roses to the yellows of the squash flowers: it’s beautiful. Throughout the seasons you take great care with each flower and each fruit. And the reward is greater than you could have imagined.

I hope you see where I’m going with my little education allegory. As my own child was quickly approaching school age, I knew I had to listen to my instincts. I knew I wanted him to be somewhere he could thrive. We knew the public schools weren’t right for our family. And given my background as an educator, not to mention the way I feel about alternative education, I knew I had something to contribute.

I have been trained in the Montessori method, which is rooted in values like independence, internal motivation, and hands-on experiences. Maybe I could have taken a job at a nice Montessori school. Happily, though, a friend introduced me to Ariel Miller, who had recently started a middle and high school program called Bronze Doors Academy. She met with me and expressed her desire for someone to begin a new program in the same building for younger students. The idea was daunting, but I felt this was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. Could I be an educational entrepreneur?

I could easily have said no to this question. I had to ask myself what was holding me back. Was it that I didn’t feel qualified? Or was it simply a fear of failure? I decided to channel what I had learned about other successful people and take a chance. Success doesn’t come to those who are unwilling to take risks. I allowed the idea of the school to germinate in my mind, and I started piecing things together bit by bit. After several weeks, what would become The Soleil School started to take shape.

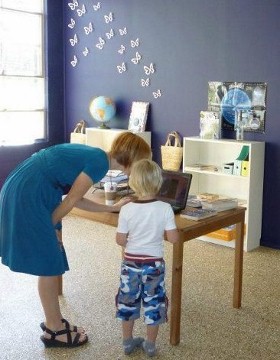

Now, as we’ve begun our first full school year, I am delighted at what is emerging: Students at The Soleil School are part of a family and school community. They are encouraged first to pursue areas most of interest to them and explore outward from there. So we begin by setting goals. Taking what I learned from my training in the Montessori method, experience in project-based education, and my appreciation for Howard Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences, I have devised a foundational philosophy called the Whole Learning Framework. It is a holistic approach in which students are encouraged to develop through a process of continuous discovery. By allowing them to work toward personal goals—which are set with guidance by both parents and the guide (me)—the students are intrinsically motivated. Contrast this with a quizzes-and-pellets method in which students are rewarded for conformity and regurgitation. In keeping with the “soleil” (sun, in French) theme, we’ve created ten learning areas in the classroom, which we call “satellites.” These subject areas revolve around the children (not the other way around). The satellites are not exhaustive, but they’re designed to let kids visualize, categorize, and contextualize different paths to learning discovery that are open to them.

In keeping with the “soleil” (sun, in French) theme, we’ve created ten learning areas in the classroom, which we call “satellites.” These subject areas revolve around the children (not the other way around). The satellites are not exhaustive, but they’re designed to let kids visualize, categorize, and contextualize different paths to learning discovery that are open to them.

We began this year by talking about the idea that the students are on a “quest.” I asked them to think about the question: What is your quest? Our first project was to create a “quest comic.” Each student was to come up with a main character who has strengths and weaknesses. Of course, the main character sets out on some sort of quest, where her strengths are to be employed and weaknesses overcome—all to reach a goal and overcome obstacles along the way. In this way, the students are able to use their creativity to delve deeper into the metaphor of the quest.

This idea will permeate what we do, whether it be academic, social, or spiritual. Ultimately, I believe in what is happening at The Soleil School. This is my quest, after all. We are different from a Montessori classroom in that we embrace technology, imagination, and collaboration. But the inspiration from Maria Montessori is certainly present in the philosophical underpinnings, in that my role is not so much a teacher but a guide. I follow the students, observing and encouraging each. I believe in them and I stress self-reliance even as I guide them. Their goals should be challenging, but realistic. Unlike most traditional forms of education, The Whole Learning Framework provides tools for creating a highly individualized curriculum based on the passions and needs of each child. We are here—and we’ll continue to be here—because we believe every child is unique, beautiful, and ready to thrive.

Carly Borders