The mechanics of cultivating growth mindset

/Srinivas Jallepalli is the author of Education Empowered: A Holistic Blueprint for Building Better Schools and a Better World. He also founded Sankalpa Academy, a growth-mindset school created to offer gifted-level education to all children, and cofounded the Higher Orbit Foundation, a nonprofit that promotes educational equity. We asked him to share some thoughts on “growth mindset” based on his extensive research for the book.

If you stand on a street at dawn, you can feel the city waking up and everything feels possible. Childhood is like that. It isn’t one long day; it’s a series of early mornings—“windows”—when the brain is unusually ready to wire new beliefs and habits that can last a lifetime. The most powerful of those beliefs may be: I can accomplish anything.

For their landmark study of language acquisition in the early years, Betty Hart and Todd Risley sat on many living-room floors and watched and listened. Their observations revealed something so basic that it might be easy to overlook: a stark difference in how much and how richly adults from different backgrounds talked with their children. The gap wasn’t just in word count—it was in conversational turns, encouragement, and the sense that a child’s voice mattered. It turns out that these early exchanges were highly correlated with vocabulary growth over the years, school readiness, and even achievement in higher grade levels. But the greatest benefit is in building identity: repeated serve-and-return talk teaches a child: My ideas are worth exploring.

Other scholars—Garcia and Otheguy, Flores and Rosas, and Faltis, for example—also point to issues with schooling that compound the challenges children from minority communities face. They argue that a cultural mismatch between families and a school system rooted in middle- and upper-class White norms is a key deterrent in the United States for these communities. Incidentally, evidence from feral and institutionalized children, Maria Montessori’s work at the Scuola Ortofrenica, and significantly higher scores for homeschooled children on the Piers-Harris Self-Concept Scale underscore the central role of enculturation, agency, and identity in human development (Education Empowered).

“Your beliefs become your thoughts. … Your values become your destiny.” This inspirational quote, traditionally attributed to Gandhi, sums it up well. This idea isn’t a cliché, it isn’t hyperbole. It’s neurological wiring in action. In the language of Education Empowered, subconscious programming happens when a message is repeated with emotion and social proof. If a child repeatedly hears, “You’re not a math person,” that phrase gets stored under truth and will silently steer choices for years. If a child repeatedly experiences “When I try strategies, I learn,” that becomes the stored program. The window isn’t just age; it’s recency and frequency—the density of messages during sensitive periods.

Education Empowered uses the story of Hermione and the House Elves in the Harry Potter series to make a crucial point: the chains that bind are often the scripts we don’t realize we’re reading from. The elves aren’t weak; they are programmed—by the world’s expectations and their own rehearsed self-talk. Hermione doesn’t just free the elves; she invites them to imagine new roles and practice them until they feel natural. This is precisely how growth mindset works in children.

How can we benefit from this understanding? The Department of Public Health in Georgia took the lessons from Hart and Risley’s work and acted. Their innovation was disarmingly practical: using the WIC program—where nearly every infant and caregiver already shows up—to coach parents on language enrichment and parent-child interaction. No new app. No new building. Just reimagining diaper changes, bath time, and grocery trips as micro-seminars in brain building. Coaches help caregivers narrate what they see, ask open questions, wait for the baby’s response, and mirror it back. Because it’s anchored in real routines, the coaching sticks. It’s not “homework”; it becomes home. And when caregivers change the soundtrack of daily life, children internalize a different story about themselves: I am a participant, not a passenger. This narrative offers an excellent start. If parents and schools then follow up with reading materials that are enriching, engaging, nuanced, and inspiring, we are well on our way to wiring confidence, high expectations, grit, and courage into our children.

The following four windows of opportunity for fostering growth mindset make the process relatively concrete.

Birth to 3: Wire confidence through identity.

This is the Hart & Risley era. Babies aren’t keeping score of correct answers; they’re counting turns. Narrate (“I’m zipping your jacket—up, up, up”), name feelings, and practice wait-time. Celebrate effort (“You kept trying that sound!”). Every serve-and-return is micro-proof that initiative matters and the child’s ideas matter.Ages 4–7: Script values and inspiration through play.

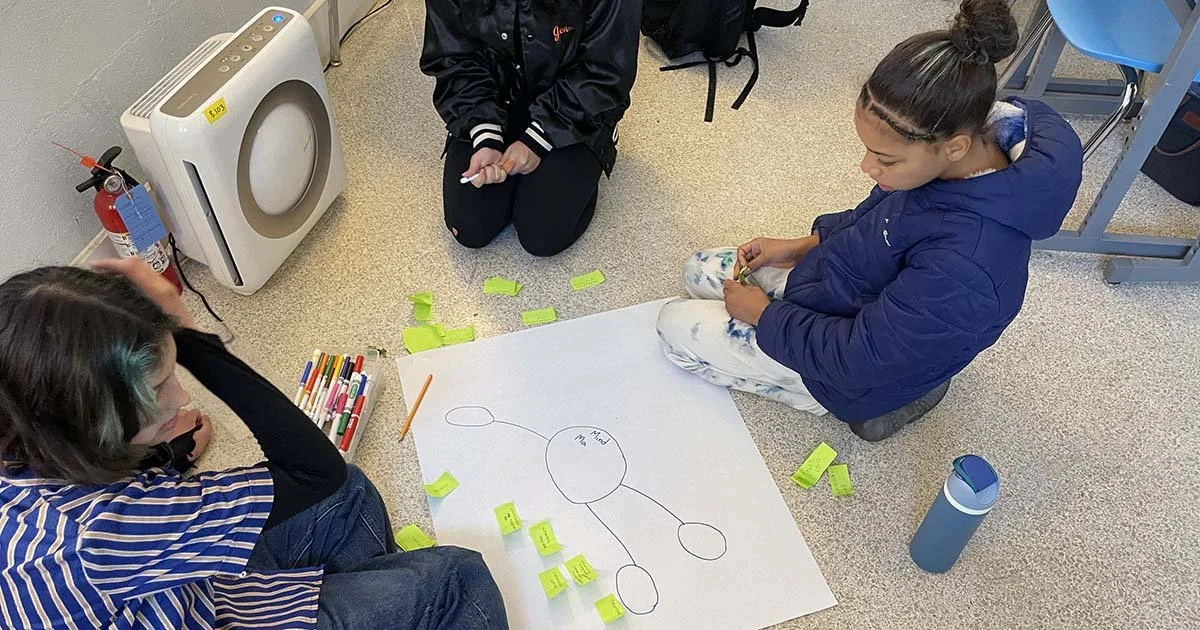

Children try on roles the way actors try costumes, and it helps to minimize cultural misalignment. Offer challenges with visible feedback: puzzles with multiple strategies, invented spelling that improves every week, stories with values that inspire. Label process not person: “You tried two ways,” “You asked for a hint.” These phrases write the growth script line by line.Ages 8–12: Make struggle normal and strategic.

Teach the practices behind progress: spacing, retrieval, worked examples, and reflection. Allow them to confront options, multiple choices, irony, hypocrisy, and strategy. Invite students to annotate their setbacks: What did I try? What will I try next? Turn “wrong” into data. When adults model revisions in their own work, children learn that improvement is a professional skill, not a personal rescue. Mindset dies when schedules deny second tries.Adolescence: Align belief with purpose.

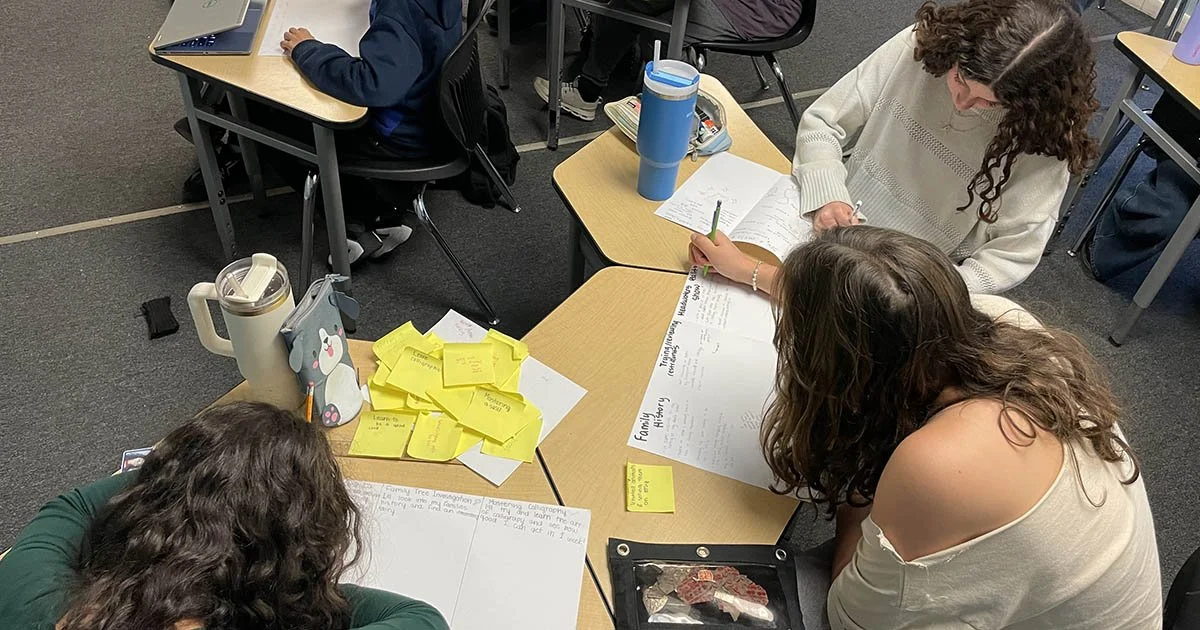

Teens will work incredibly hard for something that matters to them. Enable them to experience agency repeatedly. Link growth to contribution: tutoring a younger student, building a community resource, or pursuing a project that solves a real problem. Help them experience freedom as an opportunity to make a difference.

Hart & Risley showed that early talk forecasts later outcomes, but the deeper lesson is agency: children who are invited into conversation learn that their efforts can move the world. Georgia’s WIC-based coaching proves the solution can be elegant and equitable—bringing brain-building into places families already trust, for example. Education Empowered adds the blueprint: expose the invisible scripts, replace them with rehearsed, purposeful roles, and let children practice freedom with guidance. When we stack these pieces, we don’t just close “gaps”; we open windows—again and again—until a growth mindset is not a slogan but a lived, daily rhythm.

The dawn is already here. Our job is to step out and build a new world.

Srinivas Jallepalli | Education Empowered